Ms. Holmes and Ms. Watson – Apt. 2B

Detective fiction: A Timeline

1829: London gets a police force

You can't have a detective novel without detectives! Previously, policing was done by "constables" who reported to magistrates. Soldiers would be deployed when there was civil and political unrest. Sir Robert Peel proposed that a professional police force be formed in the London area. New York City follows suit and using a similar policing model creates its own force in 1845 (Britannica).

1841: "The Murders in the Rue Morgue"

Edgar Allen Poe is often credited with writing the first detective story. In this short story, Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin investigates the murder of two women who where killed in their home in Paris. His unnamed friend narrates the story and helps him solve the case (sound familiar?). Dupin appears in two more of Poe's stories (Britannica),

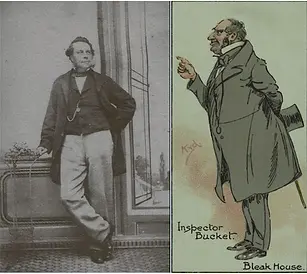

1842: Scotland Yard forms the Detective Branch

This first Detective Branch is composed of only 8 officers. The public was very weary of "plainclothes" policemen spying on them, but slowly these officers were able to win their trust. Some of these officers even inspired fictional detectives. Detective units in the United states are formed later in NYC (1857) and Chicago (1861). London's Detective Branch becomes the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) in 1878 (Britannica).

1887: A Study in Scarlet

Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson enter the chat in 1887 in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's novel, A Study in Scarlet. Doyle, much to his chagrin, will continue writing of Sherlock's cases until the 1920s. Before he retires, he will have written 62 Sherlock Holmes' stories (4 novels, 58 short stories) (The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia).

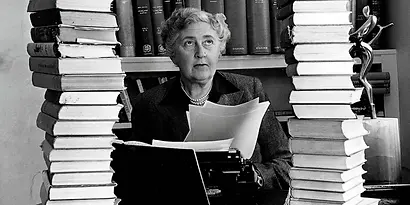

1920-1940: Golden Age of Detective Fiction

All hail Agatha Christie, queen of this genre. During her lifetime, she publishes 66 detective fiction novels and 14 short story collections. She also creates two of the most famous fictional detectives: Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple. She is still considered by many to be the best selling fiction writer of all time (Martin). We are also introduced to another famous detective in the 1930s, Nancy Drew (Random House).

1960-70s: Child Detectives

Following Nancy Drew, during the 1960s more child detectives grow in popularity. Meet Leroy Brown, aka Encyclopedia Brown, his bodyguard Sally Kimball, and Harriet M. Welsch, aka Harriet the Spy (Panovka). We also see detective fiction become more and more popular on television with shows like Scooby-Doo.

1990s: John Grisham

John Grisham starts publishing in the late 80s, and helps popularize the legal thriller subgenre. His first novel, A Time to Kill, was an instant bestseller. It was adapted to a screenplay in 1996 and stars Matthew McConaughey, Samuel L. Jackson, and Sandra Bullock. Grisham continues to publish bestsellers today (Britannica).

2000s-Present

Detective fiction and all of its related genres and subgenres, continues to be wildly popular today. Famous fictional detectives from the Golden Age and before are constantly being revived, adapted, and revamped. Look through the gallery to see some of the most popular contemporary detective fiction media.

Why is it so popular?

Philosophical Approach

At the beginning of the play, our narrator offers a possible answer to this question:

"I think what we find satisfying about any detective story, be it ever so--"original" is the idea that there are indeed pattern behind--life's distressing mysteries. That 'everything happens for a reason'" (1-2).

In her Times magazine article, "Why Mystery Books Are So Satisfying," Tana French proposes a similar answer:

"In a world that can often be chaotic and reasonless, we need these stories. During the first COVID shutdown, I was popping Agatha Christies like Smarties, and I talked to a bookseller who said they couldn’t keep her novels in stock. We need to believe that sometimes things can fit together and make sense, even when that seems impossible; that someday our crisis will end and we’ll be able to leave it behind. The clean resolution offered in the structure of these books—A kills B, C finds out whodunit—makes mystery the perfect genre to speak for the hard-won triumph of order and meaning."

Tana complicates this idea by pointing out that there are mystery stories where questions are left unanswered, the killer isn't caught, or solving the crime makes the situation worse rather than better. She argues that these books are also appealing to us because they allow us to explore the complicated ideals of truth and justice and life and death.

"When we fall in love with mysteries, it’s both those things we’re falling in love with: the hard-won sense of order, and the unanswerable questions."

Scientific Approach

Summary of a 2010 study titled "High on Crime Fiction and Detection":

Crime fiction engages our dopamine-driven "seeking emotions" by tapping into the brain’s reward system, creating a compelling and immersive experience. This engagement is achieved through intricate depictions of investigative procedures and intense emotional scenarios, mirroring the brain’s natural responses to foraging and hunting. The genre excels at activating these seeking behaviors, making the process of unraveling mysteries both thrilling and satisfying.

Additionally, crime fiction often offers depersonalization of traumatic events. By focusing on a "detective" character who is often distant from the victims, viewers, readers, and listeners are able to focus on the problem-solving rather than the emotions of the crime.